Life History & Behaviour

Life Cycle and Reproduction

Placida dendritica, like all sacoglossans, is hermaphroditic, meaning that all individuals have both female and male sex organs. The penis is located in the head, to the right of the buccal mass (mouth and pharynx) (Gascoigne, 1974). Sperm is injected into the bursa copulatrix of the conspecific (for further information, see Anatomy and Physiology tab: Reproduction). Eggs are laid on green algae and have a relatively short hatching time of 2-28 days (Clark, 1975). Egg clumps have been found on algal species in the genus Codium (Clark, 1975: Trowbridge, 1992). P. dendritica eggs hatch into planktotrophic larvae, which spend a relatively long time in the water column before settling (Goddard, 1954). This long planktonic swimming phase increases the dispersal capacity of this species. P. dendritica larvae detect cues from their algal food species, which stimulates settlement (Clark, 1975). Settlement and metamorphosis occur throughout spring and summer, and juveniles reach sexual maturity in less than one month (Trowbridge, 1989).

Defences

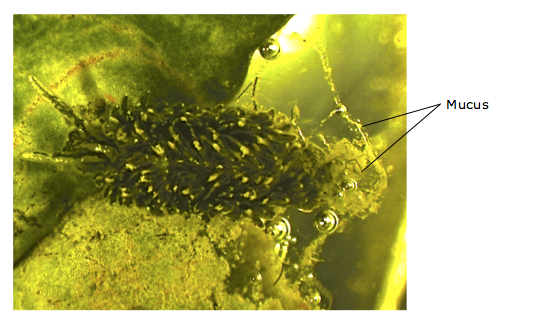

Sea slugs differ from most other molluscs in that they do not possess a hard outer shell. Without this mechanical defence, these animals have developed different defensive strategies to avoid predation. Placida dendritica utilises both behavioural and chemical defences. This species feeds on green algae, and is able to retain the algal chloroplasts in its digestive system (Maeda et al. 2010; Marzo et al. 1993). Consequently, each animal is cryptic against its algal host. Furthermore, the cerata (see Physical Description tab) of P. dendritica contain multiple multicellular mucus glands. These glands produce copious amounts of slime that contain the polyprionate metabolites placidene A and B, which have been found to be toxic to various potential predators (see photo (a)) (Marzo et al. 1993).

Photo (a): Placida dendritica specimen, which is camouflaged against the algae it is sitting on, and is secreting mucus (labelled). Photo taken by Alison Carlisle at the University of Queensland Heron Island Research Station.

Feeding

Placida dendritica, like all sacoglossans, is a specialist herbivore. This species has been found feeding on the macroalgae Bryopsis corticulans, Bryopsis pulmosa, Codium fragile, and Codium setchellii (Trowbridge, 1997). P.dendritica pierces holes in the algal cell walls using a specialised radula tooth (see Anatomy and Physiology tab: Radula), before sucking out the cell sap (Clark, 1975). This sap includes the algae's chloroplasts, which P. dendritica retains in its digestive epithelium (Marin & Ros, 2004). These chloroplasts, however, are not functional. Consequently, P. dendritica does not exhibit kleptoplasty, unlike a number of its close relatives (Evertsen & Johnsen, 2009). This sap-sucking method of feeding is characteristic of sacoglossans. P.dendritica moves around its algal host via wave-like contraction of its muscular foot. This crawling locomotion is aided by the secretion of mucus.

Habitat preference

Placida dendritica occur on the macroalgae hosts on which it feeds (see previous section: Feeding).

Experiment

On Heron Island (Great Barrier Reef, Australia) in September 2013, I conducted a short behavioural experiment on the habitat structure preference of the Sacoglossan sea slug, Placida dendritica. A total of six slugs were collected and used for experimentation. All experimentation was conducted over a three day period in the laboratory at the University of Queensland’s Heron Island Research Station.

Methods

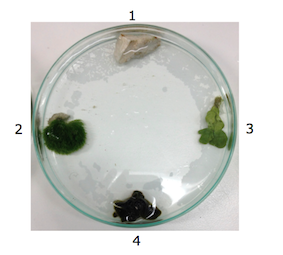

A total of six one hour trials were conducted to asses habitat structure preference of P. dendritica. Six large round petri dishes were numbered from 1 to 6, and four ‘habitat structures’ were arranged randomly, but evenly spaced, in each dish (see Photo (b): experimental set up). The empty spaces in between each habitat structure were used as controls. The habitat structures were obtained from coral rubble from the reef crest on Heron Island. The six slugs were also obtained from this area. Coral rubble was broken down into small pieces with a chisel and hammer until the necessary habitat structure was extracted from the rock.

The four structural habitats used are as follows (for images, see Photo (b) below):

1. Plain rock (calcium carbonate)

2. Grass-like algae (Chlorodesmis sp.)

3. Light coloured flat algae (Halimeda sp.)

4. Dark coloured rounded algae (Codium arabicum)

Photo (b): Experimental set up with habitat structures: 1= Plain rock, 2= Grass-like algae, 3= Light coloured flat algae, 4= Dark coloured rounded algae.

Each of the six slugs was contained in a separate housing dish and was assigned a number from 1 to 6. At the commencement of each trial, each slug was placed in the centre of its corresponding dish number. Slugs were transported into experimental dishes using a large pipette. This method was chosen because it was considered less stressful for the animals, as it somewhat simulated natural wave action. Throughout the hour-long trial, the direction in which each slug moved was recorded, along with the time at which any individual arrived at one of the habitat structures. Data was analysed using a chi-squared test.

Results

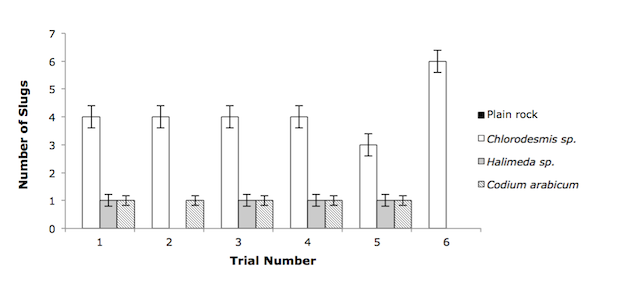

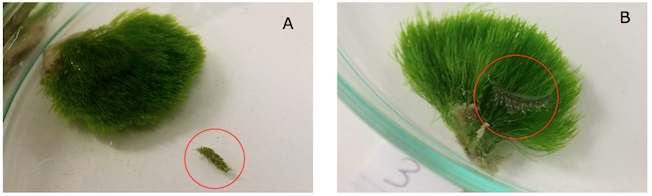

P. dendritica slugs appeared to favour habitat structure 2 (grass-like algae) more than on any of the other habitat structures (See Figure 1 and Photo (c) below). The first four trials ended with four slugs (out of six) on habitat structure 2 (grass-like algae). The fifth trial ended with 3 slugs on habitat 2. At the conclusion of trial six, all slugs were in habitat 2. No trials ended with slugs on habitat 1, plain rock. In trials 2 and 5, one of the slugs was moving at the end of the one hour trial, and so only five slugs are recorded (Graph below). A statistical analysis was conducted to determine whether the number of trials that ended with slugs on habitat structure 2 was significant. However, the test proved non significance (Chi-square, p=>0.05). In general, I observed that when slugs arrived on habitat 2, they mostly stayed there for the remainder of the hour. This also occurred, but less frequently, on habitats 3 and 4. In many cases, slugs that reached either habitats 1, 3, or 4 moved off to another habitat structure shortly after arriving (within 5-10 minutes). This also occurred with habitat 2, but less frequently. Slugs always moved towards a habitat structure, and did not hang around in open water apart from when travelling between habitats.

Figure 1: Habitat structure preference of Placida dendritica. The number of slugs that ended up on each habitat structure at the end of each hour-long trial. Legend shows four habitat structures: plainrock, grass-like algae (Chlorodesmis sp.), light coloured flat algae (Halimeda sp.), and dark coloured rounded algae (Codiumarabicum). Error bars show standard errors.

Photo (c): Placida dendritica approaching habitat structure 2, grass-like algae (A), and on habitat structure 2 (B). Slugs are circled in red. Photos taken by Alison Carlisle at the University of Queensland Heron Island Research Station.

Discussion

This short experiment had some limitations, however, it does provide some interesting potential directions for future research. The statistical results of this experiment found that P. dendritica does not significantly prefer one habitat structure over any of the others. However, observations taken during this short experiment suggest that P. dendritica individuals from the reef crest on Heron Island prefer grass-like algae habitats over non-grassy or rocky habitats. Furthermore, algal habitats are preffered over non-algal, rocky habitats. These observations, however, are non-conclusive for a variety of reasons. Firstly, this species does not usually feed alone, but rather forms feeding groups, congregating on a single algal host. As these animals occur on the algae they feed on, this directly influences habitat preference. It has been shown that a feeding cluster will stimulate other slugs to feed as well (Trowbridge, 1991). Furthermore, group feeding on non-grass-like algae, such as habitat structures 3 and 4, may be necessary for P. dendritica, as the thick walls make suctorial feeding difficult (Trowbridge, 1991). In contrast, grass-like algae is much easier for an individual slug to feed on. In addition to this, the algae species collected were not ones that have been identified as species that P. dendritica feed on.

The experiment itself was limited by a small sample size, time constraints, and a lack of controlled repeatability of treatments. As each habitat structure (treatment) was different in each experimental dish, I could not control for any extra chemicals, bacterial or microalgal communities previously existing in and on the habitat structure that may have influenced the preference of slugs. It is likely that the small sample size of this experiment may have influenced the non significant result. Furthermore, even though animals were left alone as much as possible, and despite the use of the pipette technique for transporting them, it is probable that the animals were under a degree of stress. Future studies should conduct experiments with a much larger sample size, and use Bryopsis and Codium species.

|